According to the International Labor Organization (ILO), there are over 450 million people who currently want a job, but are unable to get one. Many of these people lost their jobs in the pandemic, as businesses had to shut down, and incomes decreased. While this crisis was particularly damaging for those living in low-income nations, the so-called “First world” was not spared this disaster. Indeed, around 9.6 million people lost their jobs in the US, while about 2.7 million did so in the European Union.

In this period in which face-to-face interactions had to be kept to a minimum, the entertainment industry and, in particular, the concert industry, were especially affected. According to one calculation, in 2020 alone the global concert industry suffered an estimated 30 billion dollars in lost revenue. And that’s without taking into consideration the ancillary industries, like caterers, security personnel, and others.

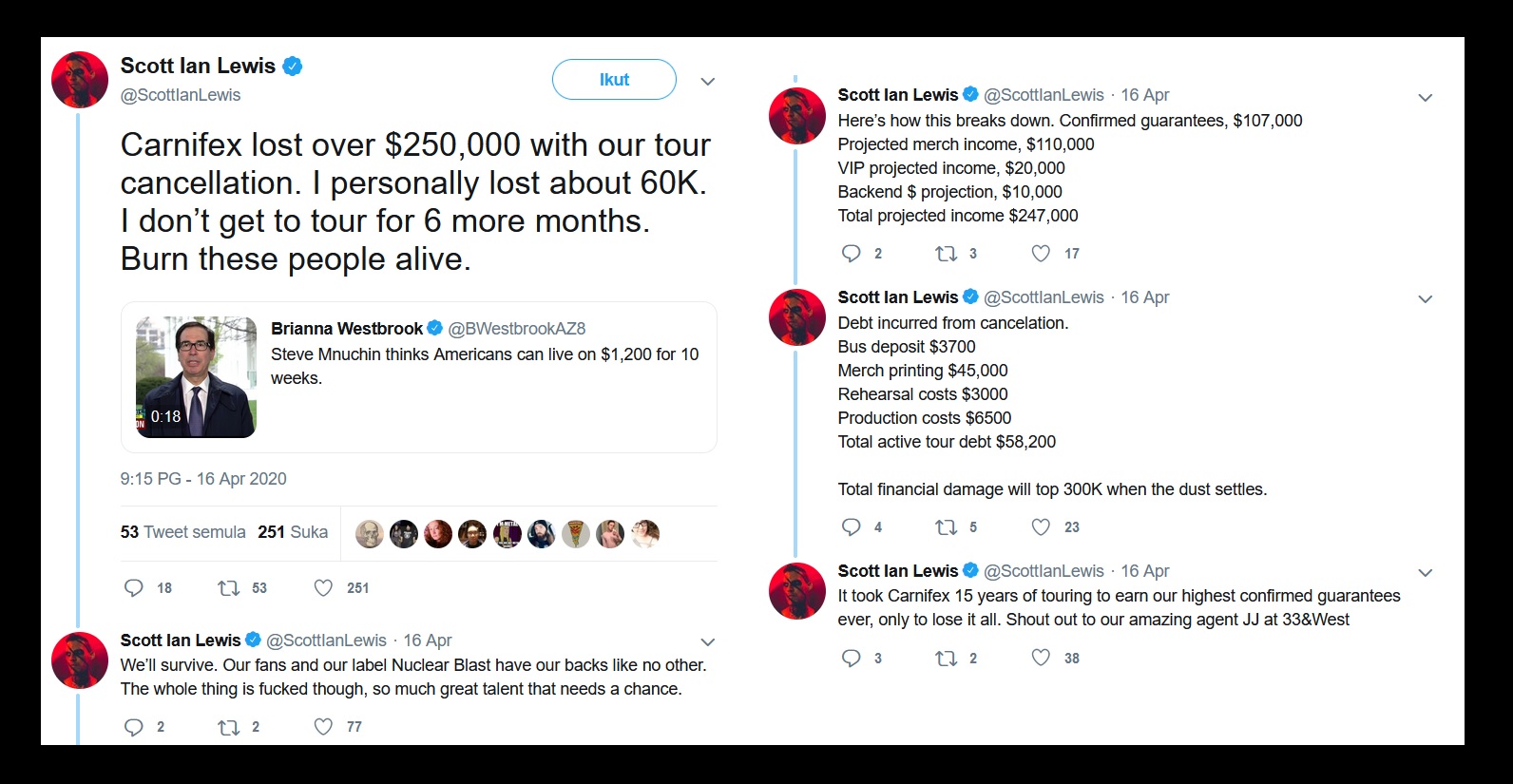

As the pandemic disrupted their ability to make ends meet, some musicians used their platforms to bring attention to their plight. That was the case of Scott Ian Lewis, singer and founder of Carnifex, who already in April of 2020 was voicing his frustration.

For musicians like Scott, the pandemic was huge financial disaster. And while being back on stage is great, it has forced him and his band to be touring almost non-stop since the lockdowns ended.

For musicians like Scott, the pandemic was huge financial disaster. And while being back on stage is great, it has forced him and his band to be touring almost non-stop since the lockdowns ended.

“Being able to work again is wonderful. I’ve been in Carnifex for 18 years, and I’ve been a full time touring musician since 2006. The music industry is a pretty unforgiving place; you have to prove yourself each year, each record, each tour, meaning that if you can’t make money and be successful, there’s no spot for you. So having fought all of those fights, just trying to survive as a touring musician, and then not being able to work because of the pandemic, was very challenging.

All of a sudden, five grown men who had been making their living off of music, and who have rent, mortgages, bills, and other people relying on them (since we have 4 full-time crew members) just couldn’t work for a living. Not by anything they did wrong, but by the circumstances affecting the world. Dealing with that was super hard, and we lost hundreds of thousands of dollars, not just on the tour that was canceled, but throughout that whole year. And then it’s not just about the time lost, but also about the time you lose trying to make up for the time you didn’t work. Because while we didn’t work for a year and a half, none of the bills stopped.

So, while it was awesome to go back on tour after a year and a half, because the fans had never been more supportive, the energy was great, and the merch and ticket sales were great, on the business side, we were making up for a year and a half of lost time. We had to incur a bunch of debt that we wouldn’t have normally incurred. And then the cherry on top was that a lot of the expenses in the touring business increased quite a bit: Since the pandemic, transportation has basically doubled. Fuel is very expensive now. Venues raised their merch rates. The crew is more expensive, because they are also trying to make up for their lost time.

We’re still dealing with the fallout of the financial damage that was caused by the pandemic; we’re still fighting our way out of that. Now we’re starting to get past the financial struggles we had, but the financial challenges that the industry presents as far as costs, those just keep going up. In every single tour we’ve done since the pandemic, overhead has gotten higher. So what that means is that ticket prices go up, merch prices go up, and less money goes to the band members. It’s been challenging. no question.”

Most musicians are unable to make a living directly from their music, with streaming services and record labels taking a huge cut from what they earn. As a result, the primary income for most bands comes not from the music itself, but from touring and selling merch. But just as musicians became dependent on playing shows and selling shirts and tchotchkes to fans, the pandemic allowed corporations to increase their control over the industry, and demand a larger cut.

Live Nation Entertainment (LVE) is the largest concert and ticketing provider in the world. The unholy spawn from the merger of Ticket Master and Live Nation, it controls around 70% of the live music market in the US, and it continues to expand. Indeed, according to a recent report by the American Economic Liberties Project, an NGO focused on promoting anti-monopoly enforcement, LVE controls the majority of the largest most important venues in the country, as well as most of the ticket sales.

The cancerous growth of LVE in the music industry is made even more complex by some of the money behind it: Its third largest shareholder is the “Public Investment Fund” (“PIF”), the financial arm of the tyrannical theocratic regime of Saudi Arabia. Most often associated with murdering journalists, publicly executing dissidents and homosexuals, establishing an apartheid regime against women, and committing a genocide in Yemen, the Saudi regime has entered into the entertainment industry in a direct attempt at whitewashing its crimes. Indeed, as Human Rights Watch noted earlier this year, “the Saudi government has embarked on a vast campaign to rehabilitate its image and deflect from global perception of the Saudi state as a severe and persistent human rights violator, particularly under the de facto leadership of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.”

The repulsive reality of the Saudi regime having a hand in the music industry has not gone gone unnoticed, and has made many musicians question their own role in this travesty. When Marko Hietala quit Nightwish, for example, he expressly referred to how “[b]iggest tour promoters squeeze percentages even from our own merchandise while paying dividends to [the] Middle East. Apparently some theocracies can take the money from the music that would get you beheaded or jailed there without appearing as hypocrites.”

In the post-pandemic world, musicians like Scott have felt the effects of this new reality:

“During the pandemic, Live Nation and AEG, these massive international conglomerates with billions of dollars in the bank, took advantage of the financial distress affecting local and independent promoters and venue owners, and bought hundreds of venues. And not just at the high level, not just big big rooms and big theaters, but also venues with a capacity of 400 or 500 people; bars, essentially. And what happens if you introduce all of this hyper-corporatization into your local music bar? Well, a beer is now $12, ticket prices go up, ticket fees go up (and bands are completely cut out of that revenue), and merch rates go up.”

Although they are not new, merch rates are a controversial part of live music. They allow the venues to keep a cut of the band’s merch sales. For years musicians have been raising the alarm against what they perceived as an illegitimate taking of their money (Orion, the bassist for Behemoth, once referred to the practice as something from “the Mafia”). But recently the practice has gone into overdrive. As Scott explained:

“This corporatization has been introduced into venues at all levels of the music business. Now merch rates have become very common, and they’re no longer 5% or 10%. They’re 20%, 25%, or 30%. Oh, and by the way, they’re also going to collect the local taxes, which I would guess they’ll just keep and never actually give to anybody, since I’ve never seen any proof that those funds actually go anywhere. And when you ask for any type of receipt, so you that you, as the artist, can write-off the merch rate as a deduction, they don’t want to provide you with any receipts. They don’t want any record of how much money you’ve given them. This is why we’re seeing more and more artists push back against this merch rate, because what was once 15% one or two nights a week, which I guess we could live with, is now 20% to 30% every night of the week, everywhere we go. So now it’s becoming an issue.

The merch rate is a tool that the agents and managers use to leverage a better deal for the performance. They get paid commission off the gross revenue made by the band, meaning that if I’m an agent or a manager, and I go to a venue and I say “my band needs $5,000 a night to play”, and the promoter thinks it’s too much, the agent or the manager can go back and say “well, keep it at $5,000, but we’ll give you a 25% merch rate.” So the promoter does his math, realizes that a 25% merch rate is going to be around $1,500 bucks, meaning that, in reality, they’re getting this band for $3,500. So, since agents and the managers make their money as a cut of the gross revenue of the bands, keeping the guarantee at $5,000 and giving away 25% in merchandise doesn’t affect their commission. They can make more money off the band by violating their fiduciary duty to the artist by agreeing to merch rates.

That’s what we’re seeing right now all across the music industry. And a big reason is that managers and agents are in bed with the promoters and with the venues. They don’t actually have that much of a commitment to their bands; some do, but most don’t. Their commitment is to the venue, because that band is probably going to come and go, while Live Nation is not going anywhere, so they need the relationship with the promoter. We’ve entered a territory where we’re realizing that there’s essentially collusion between agents, managers and venues, where they are violating the fiduciary duty to their artists. But artists have no unions, we have no protections, no collective bargaining. So anything goes, there are no rules in the music industry.

It comes back to this attitude that we’ve run into in the music industry throughout our entire career. The idea that all the people in the industry are hard working professionals, while musicians are basically on vacation, just lucky to be here. And I suppose you can have that attitude, but you are invalidating the people that you supposedly work for. If all the managers, agents, promoters, and labels are here for the artists, but they’re all telling the artists that their jobs are not real, while they send emails for a living, that’s the tail wagging the dog. And so you have industry people that think they’re the culture makers, the ones calling the shots, the ones putting putting their art into the zeitgeist… while in reality they just send emails for a living. AI could do their job.

Everything starts with the artist. But there are a lot of egos in the music business, and a lot of failed musicians on the industry side. And admitting and accepting that is not something that they’re going to want to do. It’s a free for all. There is no bar to entry, and there are no rules.

The pushback against merch rates recently motivated LVE to announce the “On the Road Again Program”. Named after a Willie Nelson song, it promises to eliminate merch fees from “all of [LVE‘s] club-sized venues” in the US, and also give $1,500 dollars per show to the artists playing in them. While this might seems like excellent news, a closer look at the program shows its dark underbelly. Indeed, despite the celebratory tone with which the traditional media stenographers touted the program, LVE’s own announcement states that this program will last “through the end of the year”, meaning that once 2024 rolls around, LVE will be free to simply go back to business as usual. What’s more, LVE is presenting the program as a kind of merciful and charitable move on the part of the conglomerate, taking it for granted that the practices were legitimate to begin with. But that’s not all.

As a conglomerate devoted to continue expanding its power over the entertainment industry, LVE’s actions should not be understood as mere goodwill. Instead, the On the Road Again Program should be seen as part of LVE’s strategy to continue devouring smaller venues. Even if it’s only for the next three months, most independent venues will not be able to match LVE’s “play here and get an extra $1,500 per show“, which will divert artists to LVE-owned-and/or-operated venues. This move might drive independent venues out of business, and allow LVE to take control over them.

Scott knows that the music world has changed dramatically since he started Carnifex. 18 years ago, when this machine was first set into motion, everything looked quite different.

“When I was 20, I had no idea that 18 years later, I’d still be in a band, I didn’t have that type of vision. I guess I was very focused on the day-to-day; “what’s the next show we’re gonna get?”, “What songs are we working on right now?” “are we doing everything to promote the album we’re about to put out?”. I didn’t have the ability to look into the future and predict what might happen.

When we started in 2005, the industry was quite different. MySpace was the only social media company, and it hadn’t really been adopted by all the corporate stuff yet. Businesses use social media now, but that wasn’t a thing back then. And there wasn’t even YouTube! That’s how old we are! YouTube started 2007, and by then we had already put out a full length record. It was a very different time, there was no Spotify, no Apple Music, no iPhone.”

But technological developments have not been the only challenges. Scott has been very open about his own struggles with depression and other mental health issues. In fact, depression was one of the reasons why Carnifex had to go on hiatus back in 2012. These struggles have been a constant in Scott‘s life and art, and he has used his songwriting as a cathartic expression.

“I’ve had my own arc as an individual outside of the songs, and I’ve learned things about songs I wrote years ago that weren’t apparent to me when I first wrote them. What I’ve really come to realize now that I’ve processed a lot of these different emotions, is that, really, these albums are just therapy. And if you think about what therapy is, you go and talk to someone about all the negative stuff, all the bad stuff that you don’t necessarily want to tell the people around you. And after you purge that, you actually feel better; maybe you cried, maybe you got angry, maybe you didn’t want to talk about it, but you did anyway, and then, once you got it out, you were able to start moving past it. And that’s what I’ve come to realize all these records are; they’re just therapy, they’re just about getting past these challenges and these frustrations. Those records exist to be there for the listeners, and to be their therapy, just like they were my own therapy; I was on a different side of it, but it will serve the same function if you can find them relatable.

Going forward, yeah, things have improved for me a lot internally. And I think that’s why Necromanteum in particular is a more outward-looking record. Now I’m dealing with more ambiguous and universal topics about life, existence, what comes next, purpose, meaning, and all those types of things. It’s less inward-looking than something like Graveside Confessions, or Die Without Hope”.

Necromanteum, Carnifex‘s new album, takes inspiration from the psychomanteum rooms that spiritualists and other have used to purportedly contact the dead.

“For me the jumping off point was this idea that 100 or 120 years ago, when you wanted to talk to the dead, you went and spoke to a doctor. That’s interesting when you think about that. Stuff like seances and rituals, using a psychomanteum, was all considered very intellectual, so you needed to talk to someone who had deep insight, like a doctor, in order to get those answers. That was my jumping off point, that no matter where we have been in society, we’re always trying to figure out what’s on the other side. I wonder if 100 years from now we’ll be looking back and not only think of ourselves as silly, but still asking the same questions.”

Scott’s interest in writing have not been limited to music and lyrics. A lifelong fan of comics, in 2018 he successfully crowdfunded the release of Death Dreamer, his debut graphic novel. And there’s still more to come.

“I’m a writer. I love writing. I might have prioritized writing too much in my music versus vocal performance, which is where the public interest is now at. Lyrics don’t mean that much, but I’ve always been drawn to them; from the beginning, for me it was always about the writing. Working on records is very formulaic, since you’re trapped in a certain format, so I wanted to move beyond that as a writer. So I wrote death dreamer.

As far as its follow-up, that book actually has a publisher now, which is very exciting. We’re still in the production process, but the book is going to come out. I had originally planned it as a trilogy, but now the full series is going to come out in one omnibus graphic novel, I think within the next year.

I’m still finishing writing it right now because, like I said, I’d written it as a trilogy. So I had the second book done, but when we started talking with the publisher, they said how they wanted to release it all in one shot. So I gotta go write part three right now. I’ve been writing it for the last three months.”

Necromanteum is out now via Nuclear Blast