Post Surgical Cinema is a series of indefinite length, motivated by a recent accident -and corrective surgery- that will keep me off my feet for the next 6 weeks. In this series I hope to cover films and documentaries that, for whatever reason, have resonated with me in a way that could be interesting for our readers.

Post Surgical Cinema is a series of indefinite length, motivated by a recent accident -and corrective surgery- that will keep me off my feet for the next 6 weeks. In this series I hope to cover films and documentaries that, for whatever reason, have resonated with me in a way that could be interesting for our readers.

NOTE: This article deals with suicide and mental disorders. If you, or someone you know, is struggling with these issues, please contact your local support line. Help is available.

On the morning of July 15, 1974, 29-year old reporter Christine Chubbuck looked straight into the camera and said:

On the morning of July 15, 1974, 29-year old reporter Christine Chubbuck looked straight into the camera and said:

“In keeping with Channel 40’s policy of bringing you the latest in ‘blood and guts’ and in living color, you are going to see another first—(an) attempted suicide.”

She then pulled a gun out of her purse, and shot herself in the head. She was pronounced dead the following day.

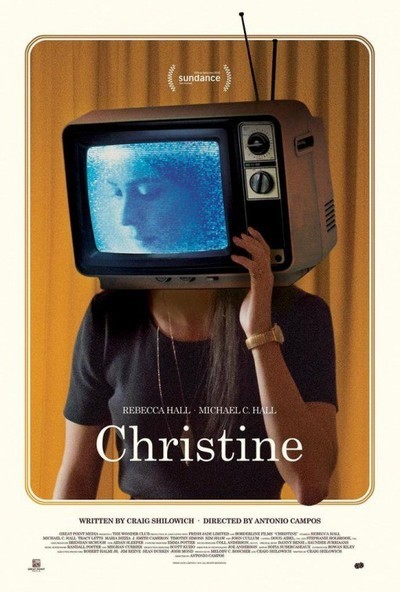

This is the story that first-time screenwriter Craig Shilowich tells in the 2016 film Christine, directed by Antonio Campos and starring Rebecca Hall. It’s a poignant tale of the struggle of living with a serious mental disorder, and which manages to cover one of the most sensationalist moments in TV history in a very respectful way, creating a raw portrayal of depression.

“The thought of suicide is a great consolation: by means of it one gets successfully through many a bad night,” said Nietzsche in Beyond Good and Evil. He was talking about the consolation that comes from knowing that, if all else fails, we still retain some modicum of control, and can choose to pull the plug. That is why suicide is often not only a sign of sadness or misery, but also of rebellion and liberation. A way in which somebody refuses to accept their lot in life, perhaps even convincing themselves that, in death, their existence will have meaning.

In Infinite Jest, David Foster Wallace (who also committed suicide) touched upon this idea, arguing that it is a mistake to simply judge suicide as a static formula in which life is necessarily better than death. Just like we understand why somebody would want to die in order to escape physical pain, he argued, we should also understand that there will also be those who make that same choice to escape mental pain.

“The so-called ‘psychotically depressed’ person who tries to kill herself doesn’t do so out of quote ‘hopelessness’ or any abstract conviction that life’s assets and debits do not square. And surely not because death seems suddenly appealing. The person in whom Its invisible agony reaches a certain unendurable level will kill herself the same way a trapped person will eventually jump from the window of a burning high-rise. Make no mistake about people who leap from burning windows. Their terror of falling from a great height is still just as great as it would be for you or me standing speculatively at the same window just checking out the view; i.e. the fear of falling remains a constant. The variable here is the other terror, the fire’s flames: when the flames get close enough, falling to death becomes the slightly less terrible of two terrors. It’s not desiring the fall; it’s terror of the flames. And yet nobody down on the sidewalk, looking up and yelling ‘Don’t!’ and ‘Hang on!’, can understand the jump. Not really. You’d have to have personally been trapped and felt flames to really understand a terror way beyond falling.”

What Foster-Wallace suggests is that suicide, in and of itself, should not be perceived as intrinsically irrational. “The terror of the flames,” in other words, can be so great, so overwhelming, that suicide does indeed become the best alternative for the victim. This is not to say that suicide is inherently positive or desirable. It merely highlights that, for someone with suicidal ideation, existence itself can be the source of untold horrors, even if only because, under a mental disorder, our perception can be distorted to such a level that we might see flames where there are only embers.

In Christine, knowing where her story is going, we are constantly trying to find the fire that will push her over the edge. In this sense, the movie plays with our perceptions, forcing us to see the world through Christine’s eyes. Up until her suicide, she is in every scene, and so we only get to experience the reality that she experiences. We are only left with her suspicions about everyone around her, her body language (that of a person who is deeply uncomfortable in her own skin), and the downward spiral of her mental health. Attached as we are to her, everybody becomes a suspect, a possible source for the proverbial flames.

At one point in the film, a gun seller explains to Christine how people live in one of 4 possible mental states: Condition White (“a state of blissful oblivion. When you’re sleeping. When you’re at home, tucked under the covers…. It’s a victim’s mentality. Condition white is for sheep”); Condition Yellow (“when you’re aware of your surroundings”); Condition Orange (You’re aware of not just your surroundings but threats); or Condition Red (“when you see the threat and you’re ready to take an action”). For Christine this wasn’t new information. She had always lived in Condition Orange, and identified everyone around her as a threat. One of the saddest parts of the story is that Christine was surrounded by people who seemed to sincerely care about her, but that she simply was not equipped to connect to them, only being able to perceive them as potential enemies.

The biggest triumph of Christine is in how accurately it shows the absolutely “meaningless” nature of depression. That its grip on someone is not always dependent on whether or not they are suffering from real, measurable negative life events, but rather on mental mechanisms that, regardless of any external input, can twist our perceptions in a way that makes non-existence seem like a viable solution. While this will not surprise anybody who has been depressed, it might provide a much-needed education for those who still imagine mental disorders are just about someone’s attitude.