The recent cultural history of Norway has been influenced by black metal. The music and scandals of bands like Mayhem, Burzum, and Darkthrone have become part of Norwegian identity. Indeed, anybody wanting to paint an accurate portrait of contemporary art in Norway would make themselves a great disservice by not paying attention to the role that black metal has played in it.

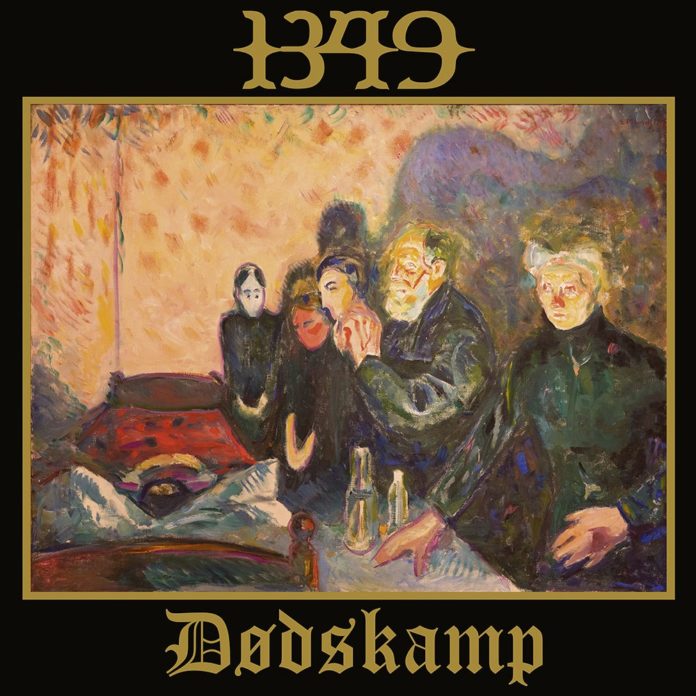

It was in the spirit of highlighting the diverse nature of Norwegian culture that Visit Norway and the Munch Museum asked a number of Norwegian musicians to use their own art to interpret some of Edvard Munch‘s paintings. When 1349 were asked to participate, the piece they chose was 1915’s “Dødskamp” (“Death Struggle”)

Edvard Munch was a mystifying figure. Shaped by a life of trauma and pain, his paintings were poignant expressions of his internal suffering. Shortly after his 70th birthday, he somberly reflected: “I was born dying. Sickness, insanity and death were the dark angels standing guard at my cradle and they have followed me throughout my life.” This wasn’t gratuitous drama. His childhood had been shaped by the both his mother and his sister dying after long struggles with chronic tuberculosis, and his art reflected this early acquaintance with death and horror. His most famous painting, The Scream, is perhaps one of the best depictions of horror and suffering ever made. “I hear the scream of nature,” he wrote about this powerful painting and, looking at it, it is hard to disagree.

In Dødskamp Munch once again placed the focus on death, looking into the room of an agonizing and bed-ridden patient who waits for death. In a small and cramped room, with the candlelight making the faces of the (soon-to-be) mourners seem somber and severe, an old man raises his hand, apparently giving the last rites to the patient. Two women in the background hold their hands together; a passive and almost sheepish pose, with an air of resignation within their sadness. They know what’s about to happen, and they’ve made their peace with it.

1349‘s “version” of Dødskamp is just as bleak as the painting. Like a big part of 1349‘s repertoire, the song submerges the listener into a constant feeling of anxiety. Imminent death, pain and suffering, the fear of the unknown, are all present here. Although Seidemann (bass), who wrote most of the lyrics, was not trying to tell the story of what’s happening in the painting, but was instead inspired by it, there’s no denying that he conveys exactly what Munch seems to have been saying:

“I can no longer see

Where chaos ends and I begin

It is cold, it is dark and there is no return

with my back towards the wall, I stare into the abyss“

Munch‘s obsession with death and mortality are perfectly portrayed by the lyrics, speaking of the “blessed death” and “the haunting agony of mortality.” This fascination with death is also mixed with the sheer horror of what’s beyond as, in true Lovecraftian fashion, our protagonist ponders about waking up in a dark abyss, surrounded by deformed and grotesque faces, all of them praying for a salvation that will never come.

In what might have been a deliberate reference to yet another pictorial masterpiece, the song ends with the phrase “Triumphus mortis,” “the triumph of death.” This is not only a perfect summary of Munch‘s work in Dødskamp (as well as in many other of his early paintings) but also the name of the 1562 masterpiece of De triomf van de Doods by Pieter Bruegel. In a somber painting where an army of skeletons storms over the world, dragging everything and everyone to the afterlife, we are reminded once again of the inevitability of death, of how we are all living on borrowed time. And yet, witnessing the chaos affecting this landscape, we can also find some consolation in the otherwise egalitarian nature of our ultimate demise: No matter who you are, no matter what you own, death will catch up with you.

Triumphus mortis.